Coaching Success – Training strategies for building strong teams

This was presented at National Association of Government Web Professionals Conference (September 2016), Confab Central (June 2017), and the Design & Content Conf (July 2017).

This was presented at National Association of Government Web Professionals Conference (September 2016), Confab Central (June 2017), and the Design & Content Conf (July 2017).

Full Transcript

When I was 13 years old, my mom took me with her to a meeting. Now, when my mom was pregnant with my older sister, she ran for a spot on our local school board. She won, and stayed on the school board for the next 18 years, so my childhood is full of memories of reading my book in the back of the room during meetings with superintendents, and union reps, and budget committees, and all the rest.

But this particular meeting, at the County Office of Education, it was a weekday afternoon, and I remember that my mom wanted me to come to it, she thought it would be interesting for me – I wasn’t just tagging along because of scheduling. The County Office of Ed was an old school, so the meeting was actually in a former classroom, and had been set up like a classroom that day.

I remember, I was the only kid there – which was pretty standard – but the rest of the group was a whole mix: there were a couple school board members, the district secretary was there, and a bunch of teachers, and some classroom aides.

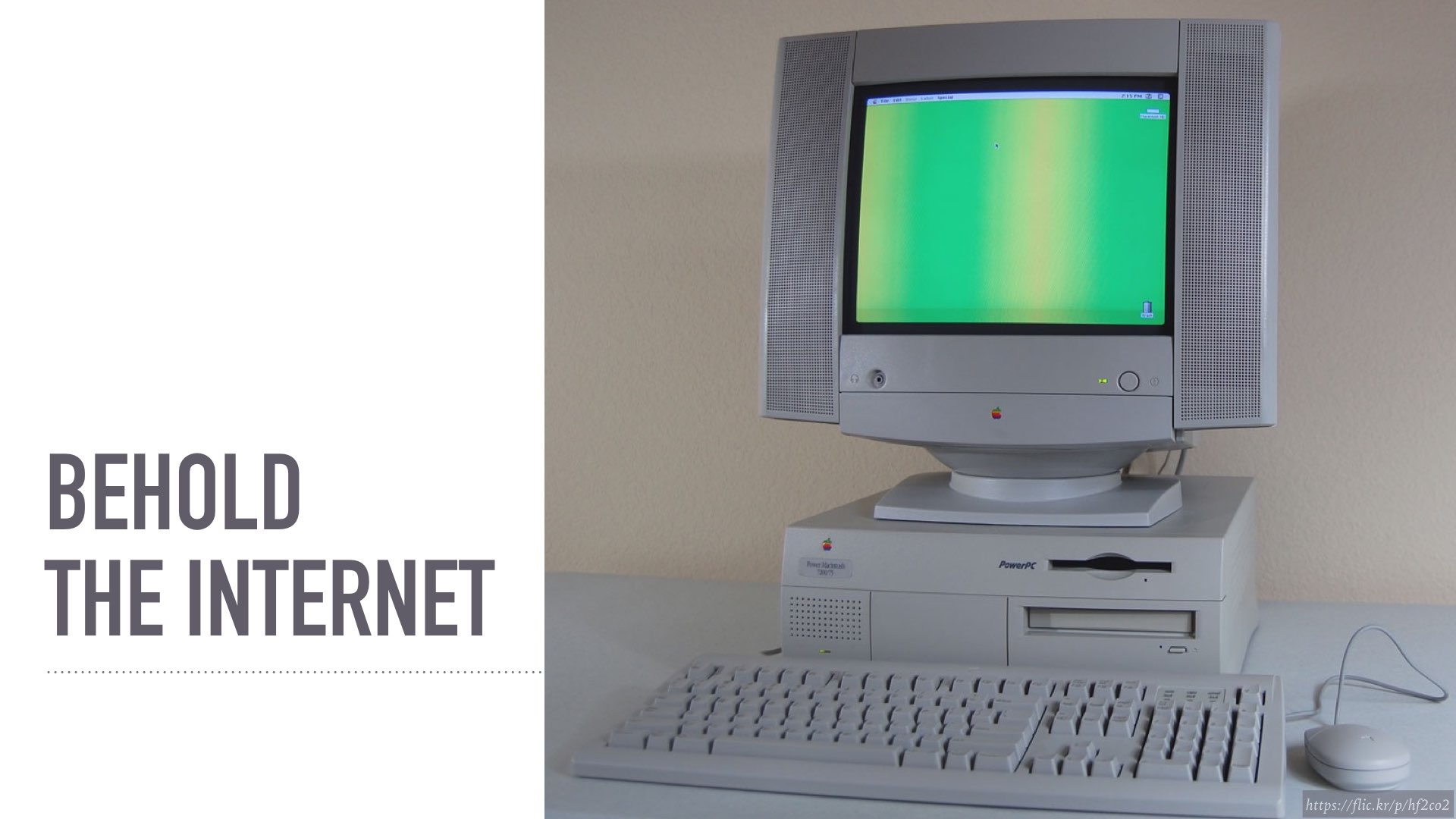

And at the front of the room, was a guy with a computer. He said that he was going to teach us how to hook a modem up to a computer, and how to connect to the world wide web. The county had gotten a grant from the state, to provide a local dial-in number and training, to get teachers and other people in the district onto the internet.

The browser of choice was NSCA Mosaic, and the webpages, they looked like this:

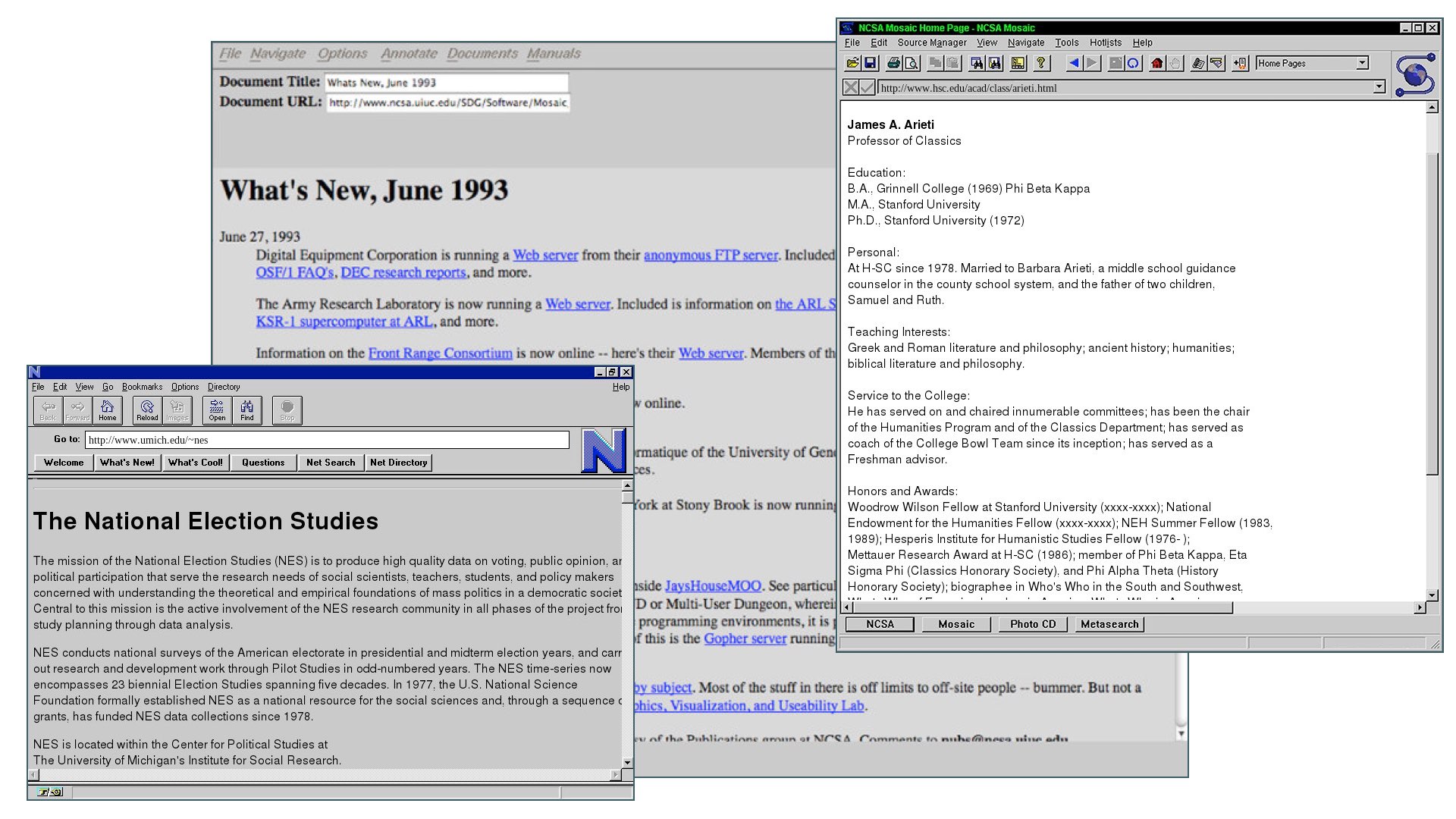

If someone was feeling fancy, they might look like this:

Y’all remember the internet back then? It was just information. Walls of text. Stuff was hard to find, it was ugly, and it was magical.

As time passed, and more and more people started getting online, we started building sites that looked cool. Now, in the early part of this phase, we were just taking our boring informational walls of text and snazzing them up a bit. But as time went on, the design tools got even fancier, and the pages got really busy.

I don’t know if any of y’all have studied architecture, or interior design, but we moved to something that sort of reminds me of late baroque, French gilded, rococo-style work.

Like: there’s a lot going on here. Every corner that could be filagreed, will be filagreed. It’s elaborate. It’s ornate! It is: hard to use. Where do you take a nap in this room?

Now, the complexity of the layouts and the ornamentation on those sites, that work really pushed us forward, in terms of tools, and web standards, and browser capabilities. And the next phase, in the world of web design, was both a reaction to, and an evolution of, those elaborate, hard-to-use sites.

We were starting to say, “OK, this is pretty. Now how can we make it easy to use?”

This is when User Experience starts to be an organizing principle for our work:

- Who’s coming to our site?

- What are they trying to do?

- How can we help them get that done?

That was a new way to frame our projects, and it led to a huge set of lovely, interesting, easy-to-use sites.

So in only a couple of decades, we went from 1) unstyled information: it got you where you wanted to go, but it wasn’t very pleasant. 2) Then we started adding colors and fonts and sparkles and tables, until we ended up with a lot of sites that were elaborate, and beautiful, but not particularly functional.

3) Then! We took the best parts of that beauty and reframed it to focus on the user. That’s where I think we are now, in the middle of this Glorious Age of User Experience.

And when we launch a site, or a project, or a set of new features, that are really focused on making things easier for our users, it feels great. I can watch people use the site and they’re able to do more, and they hit fewer roadblocks, and maybe, if we’re launching a responsive site, people are extra-impressed with how usable it is on their phones. Everything feels like a huge success, when we’re focused on the user.

And then: a few months pass. And I circle back to a new section or feature, and it’s just – a little ragged, a little confusing. Maybe there’s some content that’s out of place, or some category names that don’t make sense, or some messages that feel clunky, and things are starting to feel hard to use again, instead of easy.

When I trace it back, what this comes from, usually, is that the folks whose day-to-day work is maintaining this site (whether they’re content editors, or designers, or developers) are making decisions that aren’t in line with the original strategy for the project.

So even though the point of the whole project was, for example, to streamline an application process, or to make it easier to find program guidelines, or to connect users with the right phone number, those things are getting harder again. Those paths are becoming complicated, and confusing.

I started paying attention and noticed I was seeing this same problem, over and over again, everywhere I looked: I saw it in projects that I was leading, and in projects that I was just consulting on, and I saw it in projects I had nothing to do with. The people who are doing the everyday work on the site: they’re misusing modules to mimic things from the old system, they aren’t taking advantage of new features that solve those very same problems, and, just generally, they’re not managing the site in a way that puts the users’ needs first.

Now, none of these projects were a mess otherwise – they had solid foundations, and decent budgets, and organizational support.

They had good leaders! They also all had project leaders who were very focused on leading.

As a group of people who lead projects, you know that that work requires a very particular kind of mindset: the person in charge needs to see the path ahead clearly enough to define its edges and understand where the team going.

Especially if the project involves some sort of internal transformation: redoing your information architecture, or converting to responsive web design, or something like moving a site to a its very first CMS.

The project needs a leader. It needs someone who has been to the wondrous foreign country that is a CMS-managed site, who’s familiar with the customs and limitations and visa requirements.

Right? We want someone who knows what we’re getting into, who will help the team avoid pitfalls and potholes.

Where this falls apart, I think, is that one person is just: one person. One person who is busy, goes on vacation, gets distracted, and has other projects to deal with.

The problem with leadership is that it creates a dynamic where only one person is holding the vision. The rest of the team is freed from the obligation to hold that vision, because the leader is doing such a good job.

That one person can see the path, and the map, and the forest, and the trees – all at once – but when she needs to miss a meeting, or the team starts branching off and taking on parts of the project on their own, they often don’t have enough information to stay in line with the plan.

What I realized was that these sites weren’t being maintained well, and admins and authors were doing a poor job, because no one but me understood the strategy.

I was in a bad place: I had reached this same point on a bunch of projects in a row, where I needed the team to start ramping up and doing their new jobs, and they just weren’t up to it.

I came to the point where I was pretty sure, that the only way for these projects to succeed was for me to just – micromanage the shit out of everything.

I would edit every piece of writing, to make sure that the subheads were being used correctly. I’d sit with designers and guide their hand into choosing the best image for a new story. I would review the style guide with the developers before every tiny decision, to make sure they were choosing the right fonts and button types.

I had planned this beautiful, flexible, versatile system, and I resigned myself to believing I was going to have to leave it in the hands of people who didn’t understand anything about how to use it.

I’d resigned myself to believing, on a regular basis, that my team members were kind of dumb.

Here’s the thing about thinking someone else is dumb.

A of all) It’s just not true. It is actually, provably false.

The people on the teams that I’m working with are smart, and clever, and experienced, and good at what they do. When my gut reaction is to think they’re dumb, my gut is speaking from a place of fear, and ego, and bile, and is frankly, not worth listening to.

B of all) Even if it were true, even if someone on the team isn’t a strong writer, or is having a really hard time understanding how some new feature is going to work: How does it serve me to label them as the problem?

If I decide they’re the problem – “Jack just cannot understand our new workflow” – I’ve painted myself into a corner. Where can I go from there?

I don’t have the power to fire people. Even if I did, I don’t want to. And hiring a new person doesn’t solve the problem: they also don’t understand the new workflow.

So, at the same time I was coming to understand these constraints in my projects, over in my personal life, I’d been on… a journey of discovery.

I’d started meditating, and I got certified as a yoga teacher, and I started paying attention to the difference between the things that I was in control of, and the things that I wasn’t. The things I had responsibility for, and the things that I did not.

And I don’t think, really, that it’s possible, to start focusing on that stuff in your personal life, and not have it spill right over into your professional life. If you start your day reading the sutras, the transition over to reading your emails is not as much of a clean break as you might think.

It used to be, I would sit down at my computer and see that a piece of content has been entered wrong, or I asked for a list of something very specific, and got back a list of something else entirely.

My habit was to think, “It’s not that hard, that person’s just not paying attention, they are being dumb”.

But now I got, like, a tiny Dalai Lama sitting on my shoulder, and I can’t even get halfway through that thought before it’s short-circuited, with: “the only person I can change is myself!”

Ugh, freaking Buddha of compassion. Fine. FINE.

So, the only person I can change is myself. What does that mean for training? What does that mean for the way I lead my projects? Or teach my teams strategy?

The way I used to communicate the strategy of a project was two-fold:

1) Osmosis. If you’re in meetings with me, you should just be absorbing all of this strategy, like, via my aura and electromagnetic field.

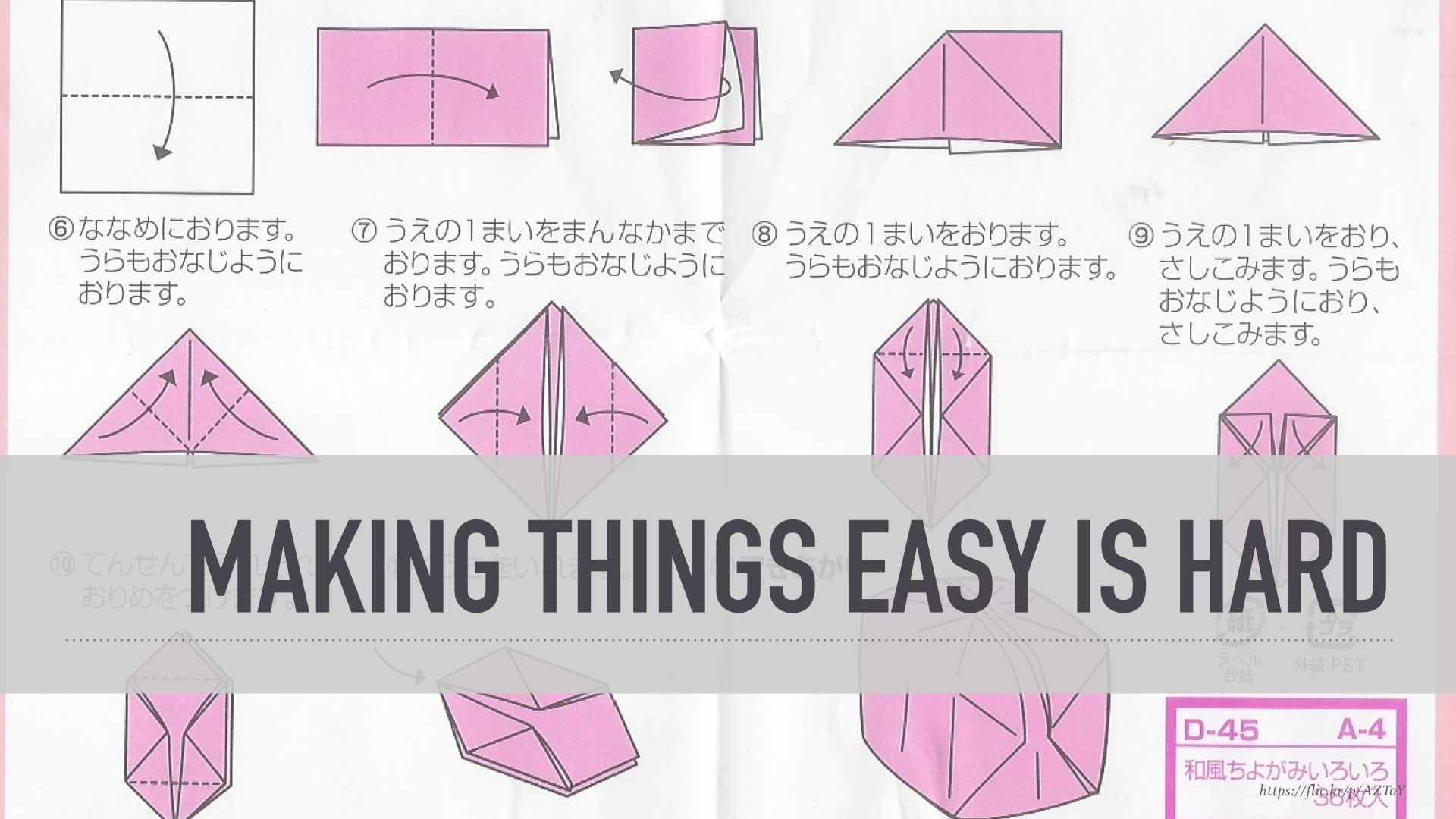

2) If you’re not in meetings with me, we’ll have a training session. It’ll be, let’s be generous, three weeks before site launch. It will be half a day of watching someone else enter fake content into an interface you have never seen before. It will radically change the way you are expected to do your day-to-day work, but! Don’t worry! There is also a long, unwieldy PDF training document for you to study at home.

Y’all, how did this become okay? We are better than this.

Traditional, one-size-fits-all instructions and training don’t work because we’re not all one size. I got colleagues working flex-schedules, splitting time between multiple departments, I got folks coming in from and going off on parental leave, I got summer interns: this whole “half a day and a PDF document” is not cutting it.

Deep breath everyone: prepare yourselves for some thought leadership.

I mentioned earlier that I feel like we’re in the Glorious Age of User Experience. And where that’s focused outward, on the people who use our sites, I think the next level of insight, the next deepening of our practice, is going to come from turning that gaze inward.

I think it’s time for us – as leaders, as strategists, as managers – to take that empathy and compassion that we have found for our users, and put that same level of attention and detail into how we run our teams, and how we train our teams.

What does that look like? We need to think about delivering:

Smaller chunks of training, that are more narrowly targeted to individual workflows, in the formats that are most helpful, in-context when people need them. We need to give our teams the space to practice working in the new setup, and we need to build in opportunities for repetition, without the sense of impatience that usually goes along with practice and repetition.

These seem pretty straightforward, right? They’re not mind-blowing. So, why haven’t we done this before? What’s gotten in the way?

Two things I think we need to address and acknowledge and deal with: urgency, and control. Let’s start with urgency.

In digital work, our world moves so quickly. Granted, you all work in the – how do I say this politely – some of the slower agencies and organizations when it comes to technology adoption, but in a lot of ways, being in a place where everything is slow is even worse: because you know that things are changing so quickly.

The Pew reports on internet usage come out every year, and the numbers only go up:

- 2/3 of Americans own a smartphone

- People do everything on their phones: banking, job applications, real estate searches, healthcare research, everything.

- Traditionally underserved groups: people of color, young adults, low income americans: basically any group other than “upper-middle-class white office dudes” are more and more likely to have their phone be their primary access to the internet.

There’s this underlying pastiche of panic and, sort of, frantic scrambling, that the world is moving, the needs of our citizens are moving, and we’re not keeping up.

You’ll note that I’m not calling it a false sense of urgency. It can be absolutely real, but being real doesn’t always mean that it serves us well.

Urgency can be a great momentum-builder; it can be the thing that gets us off our butts, that starts the ball rolling, that gets people to pay attention.

But once things are moving, urgency is the tiny devil on our shoulder, whispering things like:

- it would be faster to make educated guesses about what our users need, instead of doing real testing, or

- it’ll save time to just build this new feature now, and come back to do documentation once it’s up and running, or

- we can finish the whole redesign this quarter if we migrate all the old content as-is, and revise it later!

Real talk: urgency lies.

Urgency cares only about speed, and not about quality.

Urgency is what makes you think this IRS document is a reasonable layout for a form, or that this wall of text seems like a decent way to explain to the public what your office does.

That is some hot nonsense, right there.

Urgency is the lie that tells us it’s better to just have something done than to have it done well. Urgency drives us to think that the most important thing is to lead briskly, to get it done, to cross the finish line.

And most of us have been working with urgency for so long, that we’re pretty competent in here. It feels like some kind of normal.

But what we’ve lost in listening to urgency is any kind of sustainability. As project leaders, we always cut the corners around making sure that the whole team understands and believes in the goals and strategy behind the project.

We breeze past the part where we take the time to teach our team what this project is actually about, and then we get annoyed later that they didn’t learn it.

If you want to end up “finished”, you listen to urgency. But if you want to end up with an excellent product, then everyone on the team needs to really get the strategy.

That’s the only way you’ll ever come to a place where the designer chooses exactly the right photo for a page header, or the developer builds an accessible feature right from the get-go, or an author includes all of the right categories and metadata on their first try. They can do only do those things once they understand the project goals, and the reasoning behind decisions, in a deep, foundational, fundamental way. That kind of deep, in-the-bones, understanding, does not come – cannot come – from a training document and a webinar.

Urgency is, all things considered, a relatively easy issue to work through. It’s mostly an awareness issue.

It’s pretty easy to make the argument that our work is better when we take the time to be thoughtful. That pushing out launch by a few weeks is worth it, if what we get in return is a team maintaining the site who’s incredibly confident and skilled in their abilities.

Tackling urgency is a matter of mindfulness: we have to recognize that we’re getting sucked under by its siren song, and choose differently.

Control, though!

This is a whole different animal. Hoo, y’all, I have some feelings about control. Those feelings are: I like it. I like being in charge. I like telling people what to do. I am literally standing on stage telling a roomful of strangers what I think they should be paying attention to.

I like being the person who knows what the plan is, and not only that, but I like being the only person who really knows what the plan is. There is power there. And I don’t want to give up power! Who wants to give up power? No one does. No one! I’m pretty sure the alternative is actually death. …That’s what my ego tells me, at least. But here’s the thing about control: control lies.

Control says to me that no one else is smart enough understand the strategy, that the project is lost without me, that a stranglehold is the only way to steer.

Control is kind of a jerk.

No one understands the strategy… because I haven’t taught it to them. The project is lost without me… because I built it that way. The only way to figure out a problem is for me, personally, to deliver the solution… because I set myself up to be the hero.

None of those things are true. Or, rather, they are true, because I engineered them to be true. But control says that’s the only way to run a project, and that is a straight-up lie.

OK. So apparently I’ve decided to base part of my sense of self-worth on how rigidly I control a website project? That seems healthy. How, pray tell, can we get away from that?

Step 1, unfortunately, is that we have to look inside ourselves, to see how we got here. I’m sorry, I know many of us would prefer to skip this step, it can be – gross, in there. But we need to look, and pay attention to, all the great qualities that led us here – drive, and organization, and imagination – and also look at some of the less savory elements that got us here: competitiveness, and fear, and the need to be liked.

Dig in, a little bit, on the parts of ourselves that we are feeding when we’re in complete control of a project.

For me, being in control, being the only one who understands the whole plan, that feeds the part of me that is scared of being obsolete, the part that worries no one will hire me unless I have all the answers.

That part of me sucks. It does not actually need any more food!

So I have to make a deliberate decision: to start feeding other parts of me in a project:

- the part of me that gets excited when a team member has a lightbulb moment,

- the part that wants my friends to do well,

- the part that’s so tickled and proud when, months after I’ve left a project, they’re still making clever decisions that align with the original strategy.

Those are the parts of me that I want to feed.

Small note, I say “I made a deliberate decision”, like, that was it, one time deal. Oh, no. No. Not at all. I make, and remake, and remake that decision, all the freaking time. The fear is there, just right under the surface, and all the time it sneaks out, and I live in that place, and I make decisions from that place, and then I have a moment of clarity, and –ah, shit– and I go back, and feed the parts that I want to grow.

It gets easier. For a while there I would write every email or issue ticket or basecamp message twice. I’d write it, just the normal way, how I would always write. And then I have to take a step sideways, and edit out the fear, and add in some generosity, make that message come from the best version of myself.

When you make those revisions often enough, you can get to the point where you’re mostly starting from that better place, and all the snarky controlling thoughts stay in my head. Mostly.

Once we’ve done a little work to, well, get over ourselves, let’s look at some tactical, practical ways to help our teams understand the strategy and larger goals of a project.

As I mentioned earlier, our traditional approach to training is sitting in a room, watching someone type on a screen. If you are very lucky, your training will also involve a really crappy catered lunch.

And of course, a giant PDF training manual. Dense, confusing, and, of course, almost 100% guaranteed to out of date by the time you leave that room.

I’m willing to bet that every person in this room has attended a training like this. Most of us have probably led training like this. I don’t need to do a lot of work to convince you they’re not very effective.

There’s a caveat: this kind of training is not very effective by itself. As part of a larger suite, it’s a fine approach. Let’s talk about what else can make up the rest of that suite.

Let’s start by recognizing that there are different kinds of training.There’s:

- learning the CMS, which is what a lot of us think of as website training.

- The flip side of that is offline workflow, how content gets prepared and vetted for the site, and has nothing to do with the CMS.

- Roles & staff responsibilities: who does what, who owns each part of the process, and who owns each part of the website, what’s the maintenance plan.

- Overall strategy: user journeys, understanding the audience, why are you even doing this project at all.

This last one, this gets skipped a lot, especially when you’re talking to people in the lowest ranks of the project – they get taught how to enter, I dunno, weekly meeting agendas and minutes into the website, but they never learn who wants them there, or how people are using them.

Those aren’t all the types of training, of course, but most projects have at least this many.You can’t jam all of this stuff into a single meeting. It’s different skill sets, probably different people, it’s different brain space. Understanding that these are all separate things to learn is the first step in teaching them in a way that’s effective.

There are also lots of different formats training can take.

- Presentations, where one person is standing in front and teaching a group. This can be good for project overviews and larger goals – anything handed down from on-high.

Consider recording these – not just for people to refer back to, but also for folks who join your team later, so they can understand where the project came from.

-

Working sessions, where a group is working together to figure out how to move forward. These can be a really good approach to talking through offline workflow, working out RACI charts, and spelling out who owns each of the different parts of the process and site.

-

Documents, like our old friend the PDF manual. These are great for reference – crucial, even, when some particular bit of work is tricky, or doesn’t get done very often. I’m pretty frowny about these, in general, but it’s only because we use them so poorly.

I like to say that all documents are dictionaries: important to have around, but you can’t expect that people are going to read it cover-to-cover.

- In-line CMS training, which is vastly underused. This is when you attach help text to each of the entry fields in your CMS, rather than segregating them to a training manual. You’re putting the instructions right where they’re needed, in the editing form.

Let’s talk about making space for practice. My friend Sara Wachter-Boettcher wrote a great article called “Less Training, More Practice”, where she makes the point that

Practice is how we learned to do most of the things we’re good at: reading, writing, driving, cooking, whatever. We might have received training in a specific aspect of any of these things—Here’s how you make a cursive Q—but none of us mastered them that way.

We mastered them by doing them, over and over, until we built muscle memory—until making letterforms or parking between the lines or whisking flour and butter into a roux stopped feeling like a list of steps and started feeling natural. Until it became part of us.

When you’re teaching your teams, it’s really important to give them the space to practice.Don’t just show them on a projector how to migrate content to the new CMS, have them practice, with real content, and talk through what parts make sense and what parts are tricky. When you’re explaining how this project will improve the experience for your site visitors, don’t just present 2 use cases and call it done. Have your team members build off of your examples, and identify more things that will be improved by this project’s success. It doesn’t matter if you’ve already thought of those things; the point is for your team to start to understand, at a deep intrinsic level, why you’re doing the project at all.

Thing 4: Repetition is crucial.

This is a hard one, especially if you have any sort of background as a developer, or a project manager: we’re always looking for the most efficient way to do things. Repetition doesn’t feel efficient.

A few months ago, I was teaching a workshop. It was two days; this company was moving their website to a CMS for the first time, as part of that they were re-organizing some of their sections, and they were going to structure their content around a model that I built. They were looking at a lot of changes. It was a big project.

Now, when I built the content model for them, months earlier, I included a set of wireframes. Not as a design deliverable, not to prescribe layout, but more as a picture, a visual aid to

go along with the words and the spreadsheets that were the core of the model. The wireframes were color-coded, they were clean and straightforward.

Sometime in the middle of the first morning, the conversation circled around to The Blog. They had one, it was sort of a mess, and – I’m sure no one knows this story – it had become a catch-all for content that didn’t have anywhere else to go.

The plan, for the new system, was to dissolve the blog, and to take all of its pieces and put them in more appropriate places around the site. So we weren’t losing any content! We were going to relocate the entries to spots on the site where they’d be more useful for site visitors. So this came up in the morning of day 1, and I explained the plan, and the VP of Marketing, she was very skeptical. This wasn’t the first time she’d heard the plan, but I think it’s the first time she put attention on it? And she was like, “I don’t get it, and I don’t like it.”

It came up again twice more over the rest of the day. And we pulled out the wireframes, and we walked through how it wouldn’t change very much about how the marketing team worked, but it would allow site visitors to do X, Y, and Z. And still, she was like, “ehhhh, I don’t like this. It doesn’t make sense. I don’t know why we’re going this direction.”

So the 2nd day, we cover some other stuff on our agenda, and then I said, “Alright, it’s time to have another fight about the blog.” The wireframes were already up on screen, from the last thing we’d been talking about. I start explaining again, about the idea of that content being displayed in-context around the site, and she’s like, “OK, wait, so, Design Tips for a particular service, would be displayed on that service’s page?”

So!!! I go over to the whiteboard, and I do a quick sketch – I realize later, I have literally re-drawn the exact wireframe that was already onscreen – but I sketch out some boxes and point and say “these would go here and these other parts would go here”, and she nods, and says, “Yes. That’s exactly right. That’s just what I want. Is that what we’re doing? Because that’s what we should be doing.”

Y’all. That’s what I’d been saying for two straight days. That’s what I’d been saying for five months. After the workshop was finished, I started dissecting: how could I have helped her understand that the first time it came up?

And I realized some things I had been resisting about how teaching works, and how learning works, because I was trying to be efficient:

1) Time is not optional.

The passage of time – just straight up calendar time, letting the hours tick by – is an under appreciated ingredient in teaching.

I think about the ways we talk about learning new skills, about “making a habit” and “practicing every day”. Our assumption there is that the effort is the thing that makes a difference, but I’m beginning to suspect that the plain-old passage of time is the secret sauce. Sometimes, there’s nothing wrong with my explanation or my team members, but I have to give it a chance to percolate and be absorbed before it will click for people.

2) Repetition is crucial.

Our brains need to be taught things a bunch of times before they start to make sense. It feels inefficient, but this is not an indication that my team isn’t paying attention, or that they’re dumb, it’s plain old human nature, and I fight it at my peril.

3) Spend time with the differences.

I’ve had really good luck putting explicit attention on the differences between the old way and the new world order. I’m a nerd, so I call this work “delta training”: looking at the deltas between how you used to do things, and how you’re going to start doing them now.

Maybe we used to write everything in the 3rd-person, and now switching to 1st-person. Maybe everything used to get passed through legal before being published, and now only certain specific cases need legal review.

For example, this company with their blog that we were breaking up, it used to be the case that all videos went on the blog, because the blog was the only section on the site that could handle, technically, having video embeds.

In the new site, videos could be everywhere, but I kept saying that and it wasn’t clicking.

It only made sense once I stepped back and gave the full history: “We used to put videos on the blog because it was the only place we could put them. So all of the current processes are geared around getting videos to Allison, because she owns the blog. In the new site, we’re going to be able to put them everywhere, so our next step is to figure out who else besides Allison should learn the video upload process, so everyone can manage their own video content.”

The key here is not just to present the new way of doing things, but to acknowledge that there was an old way. People have their patterns, and their habits, and their shortcuts, and it doesn’t work to just drop off a new set of instructions and expect everyone to start following them. Help them find the path from the old way to the new way.

Lastly: There is no magic explanation. This is the hardest one for me. That second morning, when the whole blog plan finally clicked for her, I immediately started thinking, “How did I just explain that? I should keep that explanation, and use it first next time.”

I was looking for a warp zone, but: there is no secret key. I’ve been thinking of it like this:

Every person, every situation, has some secret approach, that if you can just figure out, you unlock everything.

The belief there is that I happened upon that magic key with my last explanation, and I could have saved a ton of time if I had started there.

But really? It’s more like this:

All the pieces are necessary. If I had a do-over, and started with the perfect, last explanation, it still would have taken two days. We needed to have that conversation about the writing team, we needed to talk about where users wanted to see the content. At some point, I had to redraw that stupid wireframe on the whiteboard, in real time.

Those were all necessary steps. It feels really inefficient, but – actually, what it gives me is breathing room. There is no failure in having to explain something four times.

There’s no failure in someone needing days of practice before content entry makes sense, or double checking with a coworker to make sure they’re understanding a project goal.

Those things? They’re reality. That’s how people actually work.

I could rail against that. Or, “the only person I can change is myself”. I can choose to meet my team where they are. I can choose to be a coach instead of a leader.

I will give you one guess as to which path I’ve been finding more success with.

I’m going to wind up here with a few takeaways:

Focus on your training strategy

In a large sense, all the tactics I’ve been talking about today – the different types of training, the formats you can use to teach people – they’re all, fundamentally, about not treating your team like an afterthought. We get so focused on the thing that we’re building, we forget to make a real, cohesive, thought-out plan for how we’re going to teach people to use it, or how we’re going to teach our team to manage the project without us.

For your next project – or, a project that’s still in early stages – try introducing training conversations in the very first planning sessions. Start thinking about site maintenance in your very earliest conversations: “How is the communications team going to learn to use this? Who on the development team will be available for customizing the admin screens?”

Every time a new feature gets added in the course of a project, ask again, “How are we going to teach people to use this correctly? What happens if they use it wrong?”

On the flip side of that,

Focus on your strategy training

It’s not enough for your team to be able to recite a project goal.They need to understand it. They need to understand the benefits, and the bigger picture, and the ripple effects, and the only way they can get there, is if you coach them into understanding.

What’s been working for me is to make strategic decisions out loud: to explain my thinking, explain what led me to the decision that I made and what’s wrong with the alternate choices. In telling the story of a specific decision, I’m laying out the pieces of the guiding framework. Team members hear that enough times, and they start to be able to follow the framework on their own.

And as the project progresses, my role transitions to be the person who confirms decisions, not makes them.

Now, our old pal urgency likes to get in the way of explanations; urgency says that there’s just not time to explain all this stuff, and that it would be faster not to.

Well, yes, urgency, thank you for the feedback, but, well,it’s also faster to make cheese-whiz than aged cheddar, but that doesn’t mean it’s right.

And finally,the work I’ve been talking about today that’s personal – digging into our egos and our pasts and our fears – that is legitimately terrifying work. And it can feel impossible. Here I am, encouraging you to repeat yourself over and over again in meetings, to be OK with people taking a long time to absorb new processes, to be gracious and understanding and gentle in situations that can be incredibly frustrating.

It’s important to understand that that better version of our selves, that person that is kind and generous and full of grace – that person is already there, and is always there, and will always be there.

Tapping into that version of yourself is not a matter of building a giant new skill, or filling a hole inside of you, or changing who you are,it’s more like cleaning up: clearing out the dust and cobwebs and the clutter and the mess, and revealing what lies underneath.

Launching a new site or strategic initiative is exciting, but just developing the strategy by ourselves isn’t enough. We’ve got to take our entire team on the journey with us.

Only when everyone understands the goals and the mechanisms behind a new direction – only when our teams are the heroes of our stories – do we have the foundation necessary to see our projects succeed.